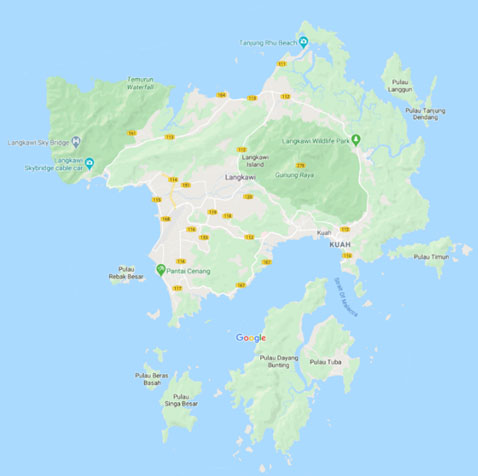

LANGKAWI, 16 October 2020: In the Malacca straits, an archipelago shines like a jewel and harbours a wealth of cultural and natural heritage. Destined to sparkle, the Langkawi archipelago is now the premier resort destination in Malaysia. The main island, eponymously named, Langkawi Island, is surrounded by many other smaller islands and two of the islands the main focus in tourism.

Before this Jewel of Kedah state became tourism-oriented, its’ economy depended on agriculture – paddy, rubber cultivation and fisheries. In the ’80s mega-infrastructure projects unfolded on the main Langkawi Island, but after years of expansion, the shift to sustainable tourism was evident as the Langkawi archipelago of 99 islands achieved UNESCO Global Geopark status in 2007.

Looking back, the massive influx of tourists brought income to the locals, but it also threatened the beauty and balance of nature. Currently, 70% of employment in the archipelago relies on tourism, but the on-going trend prioritises sustainability in tourism.

While the main island of Langkawi is always under the spotlight, there are other islands that deserve a visit. Separated by a narrow strait, Pulau Dayang Bunting and Pulau Tuba are the second and third largest islands in the Langkawi archipelago. Only a 10 to 15 minutes boat ride away from the Langkawi, these two islands have their distinctive charms. On Pulau Dayang Bunting, the Dayang Bunting Marble Geoforest Park, one of the three geoforest parks in Langkawi UNESCO Global Geopark, spans 8,261 ha. The spectacular scenery speaks for itself, attracting tourists to adore its beauty on land, lake and sea. Pulau Tuba is noted for its traditional fishing villages surrounded by lush nature.

Like gems waiting to be discovered, the slower-paced lifestyle of these two islands attracts visitors, but the challenge is to grow the economy sustainably. How to ensure that socio-economic development aligns with conservation and sustainable use of natural resources? How to preserve the intrinsic value unique to the people residing on the islands? How do island communities embrace change moving forward? These are some of the questions worth pondering when making geopark tourism in the entire archipelago a success.

Making a living on the islands

There are around 414 residents on Pulau Dayang Bunting and 1472 residents on Pulau Tuba. Together, there are less than two thousand locals on both islands.

Islanders have many practical skills, such as building houses and carpentry works. Some of them can even build temporary rafts and floating houses.

Langkawi has an agro-centric economic structure before the tourism boost in the ‘80s. Fisheries still play a crucial role in the employment of the locals on Pulau Tuba. The scene of tenacious fishers who are still out at sea even way beyond the national retirement age is still very prevalent.

Island residents provide boat or van services to tourists. With their knowledge of the local landscape, some of the Tuba residents also lead tourists on guided trips around the island.

Homestay programmes are fast-expanding. After a difficult start in late 1990, the homestay programme is now established with 30 families participating since 2018. They are popular among educational institutions. Students enjoy the tranquillity of the islands, as well as learn more about the diverse natural environment and interact with the hosts. Some locals also provide educational tours to mangroves and snorkelling sites.

This programme is something that locals want to do. Their enthusiasm will definitely fuel success and elevate the programme’s worth for visitors. However, sustainable expansion of homestays in terms of infrastructure, human resources, and management needs to be addressed. This includes repairing houses and offering training in hospitality skills and tourism knowledge.

Use of Natural Resources

Seafood is one of the main sources of food and income for the people on Pulau Tuba. The Fisheries Development Authority of Malaysia estimates that the fish landing from 2016 to 2018 was close to MYR1.1 million in value. Pulau Tuba is also one of the biggest producers of cuttlefish in Langkawi. The seafood harvest is the result of the hard work of around 308 fishers, all registered members of the Fisherman’s Association of Langkawi – Tuba and Selat.

Island forests provide communities with traditional medicine gleaned from a plethora of plants used to maintain health and cure diseases. Every part of the plant is useful for traditional treatments – leaves, shoots, bark, roots, flowers and branches. Traditional healers use only forest produce for treatments even when marine resources are readily available in the vicinity. The healers are using these traditional medicines to mostly cure fever, skin conditions and internal diseases.

Community knowledge about the Geopark concept is still rudimentary even though the UNESCO Global Geopark status was awarded to the Langkawi archipelago in 2007. The challenge is to ingrain stewardship among the communities on the two islands. Once the sense of ownership has been achieved, the geopark will be a successful tourism driver for the villagers.

There is a high potential to develop tourism sustainably as the residents are aware of the need to manage resources locally. They prefer to manage the packaged tours to the island on their own, which include tours around mangroves, caves, forests and swimming spots. Coupling this willingness with better knowledge about the heritage of the islands is crucial to promoting the place from the lens of the locals.

About Langkawi Development Authority (LADA)

Langkawi Development Authority (LADA) was established by the federal government to plan, promote and implement development on the island of Langkawi. LADA was officially established on 15 March 1990 under the Langkawi Development Authority Act 1990 (Act 423) and placed under the authority of the Ministry of Finance.

For more information visit https://naturallylangkawi.my/

Or visit www.lada.gov.my